Video Editing,

Production,

Photography,

& Corporate Storytelling

Specialty Rice of Ba'kelalan, Sarawak

4/6/2024

TV script edited for article.

Writers: Eugene Chin, Cheryl Choo

The Land of the Hornbills is known for producing some of the most sought-after agricultural commodities worldwide, including the highly-acclaimed Sarawak pepper.

Thanks to the fertile lands and optimal climate conditions of Borneo island, the pepper retains a unique aroma and subtle heat that makes it a pantry staple around the world. But in the last few years, there is one other local produce that has been making its way onto dining tables outside of Sarawak — heirloom rice. Unlike the normal variety, heirloom rice is an unadulterated grain traditionally cultivated for generations among the indigenous community. Some common heirloom varieties include black forbidden rice and red rice.

'There are at least 300 varieties of heirloom rice in Sarawak, and the most distinguished among them is Bario Rice. Its name references the place of its origin, Bario, a settlement one thousand meters above sea level and home to the Kelabit community.

'Bario Rice' is also grown in the literal heart of Borneo, in the nearby village Ba'kelalan, which is a mere twenty-minute plane ride away.

To learn more about this specific variety, we set out from our home base in Kuching to meet the Lun Bawang rice farmers - the people behind the hands that have nurtured the plains of Ba'kelalan for generations.

At the lush paddy fields, we meet the local villagers, Mutang Dawat and Sang Sigar, who regale the origin story of how this popular rice variety we refer to as 'Bario Rice' today, is in fact called 'Adan Rice'.

"Way back in the 60s they brought over Adan Rice to Miri because Bario has an airfield at that time; Ba’kelalan did not have an airport at that time" says Dawat. "That’s why this rice was exposed to the town". "Since it was marketed and people recognise it as ‘Bario Rice’ so people seem to accept that Adan Rice is Bario Rice", Sigar, a retired teacher at SK Ba'kelalan explains. "(But) the real name is not Bario Rice, it is Adan Rice." Dawat laments.

Mutang Dawat, left, and Sang Sigar, right.

Bario Rice - or should we say - Adan Rice, is a short-grain with a creamy, white colour. It is mainly cultivated in the northern lowland and highland communities of Sarawak and Kalimantan.

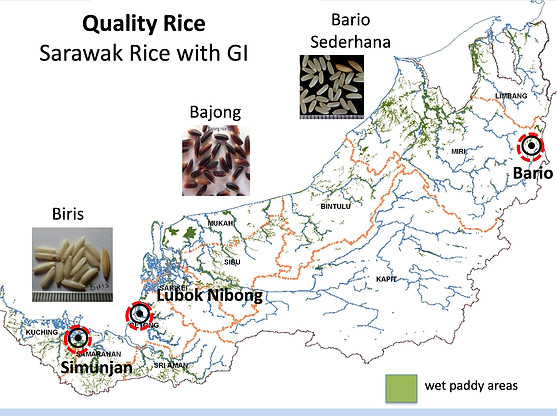

Adan Rice from Bario gained international recognition and received the International Presidia Award in 2002 from the Slow Food Foundation of Italy, which aims to protect traditional food products and agricultural methods that are at risk of disappearing. It is also one of the only three heirloom rice varieties with a certified Geographical Indication by the Malaysian Intellectual Property Organisation, whose global guidelines attributes the qualities or reputation of a produce to its geographical origin.

The other two Geographical Indication certified grains are Bajong Rice from Betong, and Biris Rice from Simunjan, which are both cultivated in the lowland. Coloured rice like Bajong is high in antioxidants and fibre and low in Glycemic Index.

Infographic by Lai KF, Kueh KH & Vu Thanh TA, Department of Agriculture, Sarawak, 2019

Cooked Bajong Rice.

We arrived in July, and the farmers in Ba'kelalan are preparing their fields for the upcoming rice planting season. In preparation for the upcoming planting season. For a settlement so remote from modernity, where even electricity is dependent on solar power, the Lun Bawang farmers believe the paddy is sustenance provided by God.

Sigar and his wife are weeding their paddy fields which have been left unattended since their last harvest six months ago, they are also accompanied by their children, who have just returned to the village for a break from their lives in the city.

Sigar, his wife, and two children clearing a paddy field in preparation for the planting.

There is only one school in Ba’kelalan -- Sekolah Kebangsaan Ba’kelalan is shared among 12 villages and offers only primary education, after which the students are sent to nearby towns to pursue further studies. It is perhaps during this time that young Lun Bawangs are exposed to the world outside their own and realise that the pasture is greener on the other side.

Photo from skbakelalan.blogspot.com

Jane Dennis, Dawat's wife, tells us that she only learned how to plant rice after her retirement, "When they are schooling, they are always away from the village so they don't experience it (rice planting), like me, after I have retired only then I know how to do harvesting". Dennis is a former headmistress at a school in a nearby town. "They (the young generation) continue their studies so they are educated, highly educated, so they had to find jobs in the Peninsula or in Kuching" she says.

Jane Dennis, a Ba'kelalan native and a former school headmistress.

Field preparation is indeed laborious work. Apart from weeds, parasitic pests — such as apple snails and fish — need to be removed from the flooded paddy fields. Removing these pests is crucial to prevent damage done to the rice seedlings.

Local heirloom rice costs more than the commercial variety. On average, one kilo goes for 17 Malaysian Ringgit. One contributing factor to its high cost is the use of traditional farming methods. Unlike commercial farms that heavily rely on agricultural machinery, the cultivation of Adan rice in Ba’kelalan is still done through traditional means, with the aid of water buffaloes.

This is a nursery of Adan seedlings. The seedlings are ready to be transplanted to the paddy fields once field preparation is done.

We returned to Ba’kelalan 5 months later. As our Twin Otter aircraft approached the runway, there was a sea of golden paddy fields below. Looks like we arrived just in time for the harvest. We reunited with Cikgu Sang and his wife, Julia Sang, who have just started harvesting the paddies in their field. Their children have already gone back to the city.

During the harvest season, many Lun Bawangs living in urban areas make the journey back to Ba’kelalan, only to return to their city homes once the season ends. More and more of the younger generation leave the village in search of better opportunities. In contrast, retirees are returning home to their villages to settle down, like Dawat and Dennis.

The annual paddy production in this village of a thousand two hundred people is estimated to be one point nine metric tons. Like most indigenous paddy farmers across Sarawak, the primary reason for rice planting is for self-sustenance and gifting on special community occasions, like weddings and Christmas. Only the excess is sold.

In the nearby town of Lawas, we witnessed a Lun Bawang’s wedding where the harvested traditional rice is cooked and served to guests. The rice was contributed by the relatives of the couple, both of whom are also farmers. The rice is typically cooked and served in tapioca leaves. The Lun Bawangs call it ‘Nuba Tenga’ in their language.

Most heirloom rice farmers still adhere to their traditional cultivation methods, and though sustainable, its small yield is unable to meet the market’s demand. And contrary to belief, the disinterest of the younger generation is not the underlying cause. The reality is, many rural farmers are forgoing the tradition and their paddy fields for cash crops like oil palm.

Accessibility is also a large concern: underdeveloped infrastructure can deter prospective investors and visitors from the area. We found the road conditions to and fro the highland villages in an appalling state.

By and large, farmers practising heirloom rice cultivation lack incentives and support from the authority to continue heirloom rice husbandry, especially in today’s fast-growing and competitive economy.

Exploring the valley, we spotted a few young people reaping and threshing at a paddy field. Perhaps not everyone of the new generation has a detached interest in farming after all. "The tradition of harvesting paddy has a long history" Aaron, the young farmer, says. "I feel that we must continue this tradition until our future generations. What if one day the old folks are no longer with us, who will continue this tradition?"

Jiren and Aaron.

Globally, consumers have become more health conscious and aware of the nutritional value of sustainable agriculture crops. And with a growing support for ethically-cultivated produce, there is a place for Sarawak’s heirloom rice yet on every pantry shelf.

Rich in biodiversity and diverse in cultures, Sarawak has the potential to be an active part of the global discourse on sustainability and food security. And perhaps, with a little introspection, we might just find that the best move towards a sustainable future, is by taking a step back to our roots.

Watch the documentary below for the story: